|

| Aquatically-adapted ornithocheiroid Ornithocheirus simus takes off using aquatic quad launch, as hypothesised by Habib and Cunningham (2010). Prints of this painting - which might be the first illustration of this launch strategy - are available from my shop. |

Many pterosaur lineages seem to have close ties with marine environments, as evidenced by biases in their fossil and taphonomic records and indications of frequent interactions with marine fish. It stands to reason that these animals would find themselves in water on occasion, and trackways made by swimming pterosaurs indicate they may have been quite at home in this medium. Recent studies by Dave Hone and Donald Henderson have cast doubt on the swimming ability of pterosaurs because their floating postures seem rather awkward, which they suggest might have impeded breathing while swimming (Hone and Henderson 2014). Their studies found that, rather than sitting atop the water with arcing necks like birds, front-heavy pterosaur bodies collapse the head and necks into the water, bringing the mouth and nostrils close to the water surface. Although initially sceptical of this idea, I must admit to at least agreeing that avian-like postures may be difficult for pterosaurs. Our expectation that they floated in a bird-like fashion - which I've illustrated several times (Witton 2013 and elsewhere) - is actually quite silly given their proportions and differences with bird morphology. Pterosaurs lack the well-muscled hindlimbs which depress the back end of bird bodies into water, as well as the flexible necks and small heads required to attain duck or gull like floating postures. Indeed, birds seem unique in their floating posture, whereas pterosaurs seem to have floated in a manner more typical of other animals. Does the proximity of their nostrils or mouths to the water surface impede their swimming ability? Maybe not, given that virtually all non-avian animals I can think of - including aquatic species like otters, crocodylians, swimming rodents, etc. - float and swim with their nostrils close to the water. As long as they have enough control over their swimming ability to clear their nostrils for respiration, they were probably fine. I see no clear reason to think pterosaurs were less competent in water than other animals, and maintain the view that some - for functional reasons - probably needed to swim to obtain the pelagic prey they did/likely did consume (Witton 2013).

But what did pterosaurs do when they needed to leave the water? Could they fly from the water surface or did they have to seek land to take off from? Anyone who knows anything about current pterosaur research knows that the leading hypothesis on pterosaur takeoff is quadrupedal launching, where the hindlimbs mostly serve to provide forward momentum, and vertical heft was provided by the forelimbs (Habib 2008) - many species of bats including vampires molossids and some mystacinids use a similar mechanism. It's worth stressing that this idea is not only supported by anatomical characteristics and positive results from biomechanical studies, but also by the fact that the hindlimbs were too weak to launch sensibly-massed pterosaurs into the air. All studies favouring bipedal launch have had to circumvent this somehow, typically by under-estimating pterosaur masses by, probably, as much as 60%. This makes bipedal launch a real no-go, whereas quad-launch has, to my knowledge, has meet all tests and predictions. We typically discuss quad-launch in terrestrial contexts, but can it work on water?

|

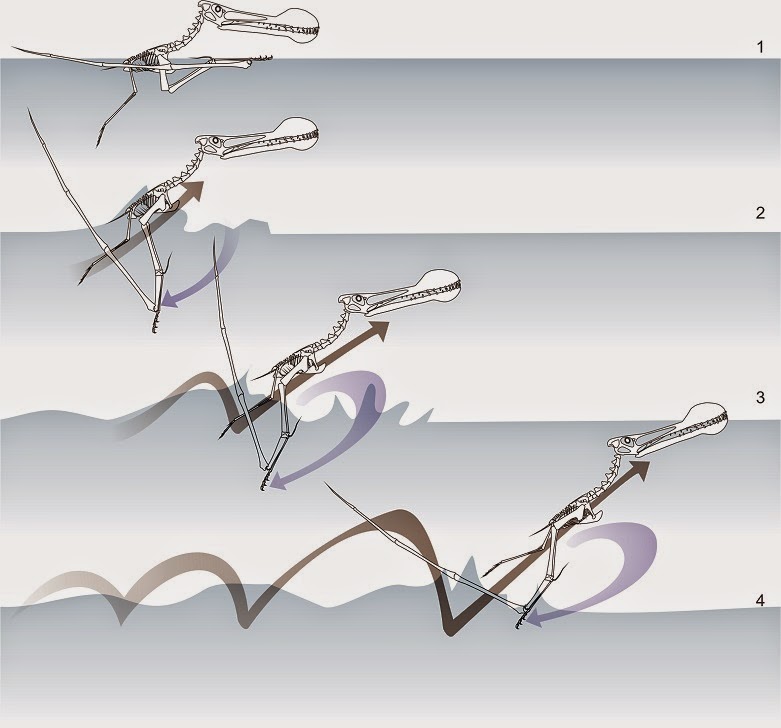

| Schematic of water-hopping quad-launch strategy, from Witton 2013. The floating posture in panel 1 might be incorrect, but the general thrust of the image is OK. |

It turns out, probably yes. According to work by Habib and Cunningham (2010), a version of quad-launch works just fine in aquatic settings. It seems that many folks have difficulty imagining how this works, but it's really not too dissimilar to terrestrial quad-launching. As with any takeoff mechanism, the the trick to water-launching is a leap providing sufficient height and speed to facilitate wing use (flapping alone doesn't really get you anywhere, and is especially ineffective at larger sizes). In this respect, it is just like terrestrial launch. An added complication of water launch is escaping surface tension, the cohesive force operating at air-water interfaces. This is where differences between terrestrial and aquatic launch become apparent, because it seems most pterosaurs were incapable of overcoming surface tension from a 'standing' (er... stationary floating) start. Their half-submerged posture and the fluid nature of the medium they are pushing against likely prohibited generation of sufficient energy for a standing launch. The solution to this is a series of hops across the water surface (above), each one providing further water clearance and velocity than the last. These were achieved, as on land, by the combined efforts of both the legs and arms. The wings are not fully deployed at this point, although the arm motion is probably showing some similarities to a flight stroke. The early stage of this takeoff might look a little like swimming with a particularly powerful butterfly-stroke, albeit one where the swimmer is emphasising vertical motion rather than horizontal. Eventually, the pterosaur is leaping across - not through - the water and is clear enough to push off fully from the water surface. For this final push, the wing is opened and flapping can start. It seems that some pterosaurs - principally ornithocheiroids - were very well adapted for these manoeuvres, showing the shoulder reinforcement, upper-arm strength and distal-limb adaptations you'd predict for water-hopping quad launchers (Habib and Cunningham 2010, Witton 2013).

Some especially powerful pterosaurs, however, probably didn't need to worry about water hops. Giant azhdarchids, which experts predict were not only fuelled by muscle, but raw awesomeness sucked out of the universe itself, were probably powerful enough to water launch without hopping (Habib and Cunningham 2010). Some also ducks have sufficient power to do this - check out the launches in this video for cracking, slow-mo examples (the second is best, at 20 seconds in. Hat tip to Mike Habib for the link).

Recently, palaeoblogosphere regular Mike Traynor commissioned me to paint pterosaur water quad-launch - I think for the first time (if anyone knows different, please let me know). The results, a 6 m wingspan Ornithocheirus simus at the apex of the launch cycle, are above and, for fun, shown in progress from my Twitter feed below. If you'd like to own a copy of this image, you can: point your internet mobile at this page.

WIP water launching Ornithocheirus. Have decided pterosaur water launch was what experts call 'very splashy'. pic.twitter.com/zwAZPYKAD1

— Mark Witton (@MarkWitton) February 21, 2015More work on water launching Ornithocheirus - now with teeth! And go-faster jaw stripes! pic.twitter.com/rIu6STmH5p

— Mark Witton (@MarkWitton) February 23, 2015Update 3 of WIP water-quad-launching Ornithocheirus. Occurs to me that this might be the first painting of this idea. pic.twitter.com/o5NfSSrzSI

— Mark Witton (@MarkWitton) February 23, 2015Update no. 4 on water-launching Ornithocheirus. Been watching lots of bird takeoff footage to get the splashes right. pic.twitter.com/sEIGNW7Qow

— Mark Witton (@MarkWitton) February 25, 2015Might be done with Ornithocheirus superaqualaunch - client approval pending. Prints should be on sale soon. pic.twitter.com/vzY5usQKiv

— Mark Witton (@MarkWitton) February 27, 2015We're not done with aquatically-adapted animals just yet. Coming soon: the surprising aquatic adaptations of our own Mesozoic relatives.

References

- Habib, M. B. (2008). Comparative evidence for quadrupedal launch in pterosaurs. Zitteliana, B28, 159-166.

- Habib, M., & Cunningham, J., (2010). Capacity for water launch in Anhanguera and

- Quetzalcoatlus. Acta Geosci. Sin. 31, 24–25.

- Hone, D. W., & Henderson, D. M. (2014). The posture of floating pterosaurs: Ecological implications for inhabiting marine and freshwater habitats. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 394, 89-98.

- Witton, M. P. (2013). Pterosaurs: natural history, evolution, anatomy. Princeton University Press.