This week sees two new pictures of mine being 'released' in one way or another. Much as I'd like to go into lots of detail about each, that realistically isn't going to happen anytime soon. I'm going to attempt a sort of 'picture[s] of the day'-style writing. I'm sure I can do it... right?

Chidumebi Browne's resting Tyrannosaurus teens

|

| Two young adult old male (left) and female Tyrannosaurus on a break from pillaging and destroying the Cretaceous, distracted by a group of ruffian moths. Concept and animal colouration by Chidumebi Browne. Prints are available. |

The concept called for a a series of moths catching the attention of the male tyrant: initially one was ordered but, even at half-size, Tyrannosaurus is pretty big, so a few more were added to make them more conspicuous. My initial thought was to use butterflies rather than moths for the role of the lepidopterans, but I was surprised to learn that butterflies don't appear in the fossil record until well after the K/Pg event. Moths have a fair, if not especially extensive Mesozoic record, so they seemed a safer bet. They certainly add an air of tranquility to the scene not featured in a lot of theropod art: well done to Chidumebi for an excellent idea.

There'll be more output from the '£100 palaeoart offers' soon, although note that the offer is now full - over-full, in fact. There's some great ideas which I'm hoping to do justice to, so thanks to all who got their orders in - the offer sold out very quickly. If you didn't manage to get something to me on time, prints are still available - wittonprints@gmail.com is the address to contact for them.

Gower et al.'s Garjainia madiba: yes, the head is that big

|

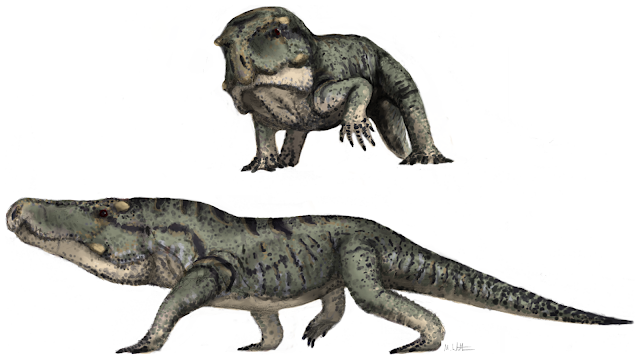

| Gargainia madiba sp. nov., South Africa's newest erythrosuchid. From Gower et al. 2014. |

Art number 2 is a life restoration of a new species of Early Triassic stem-archosaur, the erythrosuchid Garjainia madiba, described by David Gower and colleagues in this week's PLoS ONE. Unearthed in South Africa and named for Nelson Mandela ("Mr Mandela was known affectionately as 'Madiba'" - Gower et al. 2014), G. madiba has been making surprising ripples on Twitter and Facebook because of its rather enormous head. I say surprising because, for an erythroshucid, G. madiba is fairly typically proportioned - so far as anyone can tell, anyway. We don't have anything like a complete skeleton for G. madiba, although many aspects of its anatomy are represented in fragmentary specimens. It is currently distinguished from its relatives by fine anatomical details, perhaps the most notable being its large postorbital and jugal bosses of unknown function (best seen in the reconstructed anterior aspect, above). The discovery of more substantial G. madiba fossils may reveal more obvious distinction from other erythrosuchids, but, for the time being, the best we can do reconstruction-wise is show G. prima with a madiba upgrade package. Still, given how similar the two Garjainia species seem to be, this does not seem unreasonable.

Restoring Garjainia was a lot of fun because it forced a 'back to basics' approach to the artwork where David Gower, Richard Butler and I spent a lot of time discussing proportions, muscle distribution and posture. Many fossil animals - dinosaurs, pterosaurs, etc. - have been restored so often that the basic foundations of their anatomy are very well known, but this is not so for Garjainia and other erythrosuchids. A personal revelation to come from this process was evidence for enlarged areas of axial musculature on erythrosuchid skeletons, indicated by the rather tall neural spines of their necks and backs. This might give some insight into how their large heads were supported: a particularly well-developed, strong set of axial muscles. The posterior faces of their skulls are also wide and robust, providing space sufficient to anchor powerful neck muscles. But erythrosuchid anatomy was likely not held together only by brute strength: there's also some clever biological engineering at work. Like many archosauriforms with huge-looking heads, their skulls are more gracile and lightweight than they first appear, actually being fairly narrow for much of their length and riddled with fenestrae. We tried to show the former in our anterior aspect reconstruction: note how slender the snout of the animal is compared to the cheek region. The result is a head which is undeniably large, but probably much more manageable than it first seems.

For a lot more on Garjainia and other erythrosuchids, including the life restoration in situ, full descriptions of G. madiba anatomy and revisions to the diagnosis of the group, Gower et al. (2014) can be read here (hurrah for open access!). Thanks to David and Richard for bringing me on board, and congrats to them on the paper.

Coming soon: small, brown Mesozoic mammialiaforms! Yes, they are exciting. Really.

Reference

- Gower, D.J., Hancox, P.J., Botha-Brink, J., Sennikov, A.G., & Butler, R.J. (2014) A New Species of Garjainia Ochev, 1958 (Diapsida: Archosauriformes: Erythrosuchidae) from the Early Triassic of South Africa. PLoS ONE 9(11): e111154. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111154