|

| Two Wesserpeton evansae get in each other's faces, because that's what albanerpetontids did. |

You could be forgiven for thinking otherwise, but the Mesozoic wasn't just the remit of dinosaurs, pterosaurs, marine reptiles and token cool crocodiles. Many other interesting animals shared the world with these famous species, including some that most of us have never heard of. Tuesday of this week saw the (open access) publication of one such animal, the Wessex Formation albanerpetontid Wesserpeton evansae by Steve Sweetman (University of Portsmouth) and James Gardner (Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology) (2013). Many readers will be familiar with the Wessex Formation or the larger geological unit it is part of, the Wealden Supergroup, because of its frequent mentions as Britain's top dinosaur-bearing deposit. I'm sure many of us are not overly familiar with albanerpetontids, however. This isn't too surprising. To my knowledge, albanerpetontids have never featured prominently in any palaeoart or publications geared towards popular audiences and their existence is largely known only to specialists. The world's naivety to these animals was broken yesterday when Steve and James, with a little help from my painting above, finally told the world why they should add albanerpetontids to their list of cool fossil animals.

Alba-who?

Albanerpetontids are small-bodied amphibians that were fairly common components of terrestrial environments until relatively recently. The youngest members of their clan perished at the end of the Pliocene - about 2.5 million years ago - after an evolutionary run of 160 million years and attaining a wide geographic distribution across North America, Europe, Africa and central Asia. Their general lack of mention in popular press would have you believe otherwise, but they can actually be relatively common fossils. Remains of Wesserpeton are, after crocodiles, the most abundant microvertebrate in the Wessex Formation. Despite their relative abundance, their relationships to other lissamphibians have been debated because many of their fossils are exceptionally scrappy. Traditionally, they have been thought of as caudatans (salamanders) or at least very close relatives. Recent discoveries of complete and articulated albanerpetontid fossils (below) have suggested otherwise however, proposing that they are closely related to a clade containing frogs and salamanders, but not members of any extant amphibian group (McGowan 2002).

The anatomy of albanerpetontids is fairly conservative. They look more-or-less like small salamanders with short limbs and long bodies, but also possess mandibles which interdigitate anteriorly, fused frontals (bones of the skull roof) and relatively flexible necks because of a mammal-like articulation between the skull and neck. They also had scaly skin, a condition which contrasts with the typically thin and delicate skin of other amphibians. It seems that they spent most of their time burrowing through leaf litter in search of small arthropod prey, with their scaly skin preventing dessication and likely reducing the typical amphibian need for wet or moist environments. Fossils suggest that scales stretched across most of their bodies (we went the whole hog in our reconstruction and covered our Wesserpeton entirely) and onto another unusual amphibian feature: eyelids. We thought about eyelids a fair bit for our painting. The few available depictions of albanerpetontids show animals with eyes perpetually covered with scales, leaving only very small, beady eyes to see with. Steve and I noted that these animals actually have very large orbits however, suggesting that their eyes were probably reasonably sized. It seemed counter-intuitive to possess large eyes and then cover them in soft-tissue, so our reconstruction assumes that the eyelids only partially covered the eyeballs.

|

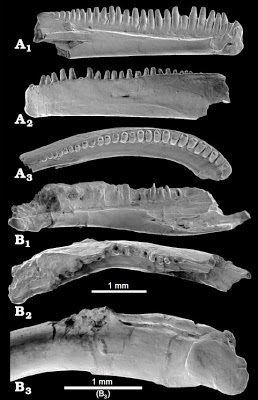

| Lower jaws of Wesserpeton evansae showing typical (A) and pathological (B) anatomies. From Sweetman and Gardner (2013). |

Small man syndrome

Initially, our plan for the press release painting was to show a single animal reclining in some leaf litter or something equally simple, but Steve suggested early on that we could work in an interesting component of Wesserpeton behaviour. Many Wesserpeton jaws show signs of trauma (above) after being broken during violent acts. The exact cause of this damage is still being looked into and will form the subject of a later paper, but a good preliminary explanation is that Wesserpeton was a vicious species which routinely fought among themselves. Modern salamanders, such as these giants, bite the heads of their opponents before wrestling with each other, twisting and somersaulting with one another to settle disputes over territory and mating access. It's not difficult to imagine such acts taking their toll on the jaws of Wesserpeton, and we thought it would be cool to show this in a press image. Preliminary attempts at rendering this struggled to show the general appearance of the animals however, as their bodies were twisted and their heads obscured by jaws. How could we show the aggressive nature of this animal without actually showing them fighting?

Finally, a quick word on the body size of Wesserpeton. We've mentioned it was small, but how small? The answer is tiny. As in, 35 mm snout-vent length tiny. This thing really puts the 'micro' in 'micropalaeontology'. We prepared another set of press images to show what this means in real life (available in different colours to suit whatever occasion you're at where you want to discuss the size of Wesserpeton):

|

| The United Colours of Wesserpeton, which is dwarfed by the palm of your hand no matter what colour you are. For some reason, this image makes me want to imagine a world without lawyers. |

I'm no expert on this sort of thing, but I'll wager that Wesserpeton is one of the smallest, if not the smallest tetrapod species known from the Wessex Formation, and probably one of the smallest tetrapods in the fossil record. It's fossils were only recovered through bulk sampling tonnes of plant debris bed from the Wessex Formation, horizons rich in plant and vertebrate remains deposited after sheetflood events, and would be almost impossible to find via surface prospecting. Those of you with excellent memories may recall that Steve's ongoing analyses of these beds have revolutionised our understanding of the Wessex palaeobiota, of which Wesserpeton is just one discovery among many.

And that will have to do for now. Next week: back to the world of pterosaurs with pterosaur mummies, as promised last week before Wesserpeton face-wrestled its way into centre stage. My plan from here on is to have some sort of run-up to the publication of my book, Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy on June 23rd, so be sure to stick around if wing membranes are your thing.

References

- Jaeger, R. G. 1984. Agonistic behavior of the red-backed salamander. Copeia, 309-314.

- McGowan, G. J. 2002. Albanerpetontid amphibians from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain and Italy: a description and reconsideration of their systematics. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 135(1), 1-32.

- Sweetman, S. C., and Gardner, J. D. 2013. A new albanerpetontid amphibian from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight, southern England. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 58, 295–324.